Advice for your next bear attack

What if we accepted hardships as callings to refine very specific traits within us?

Recently, I came across a story of two young men who survived a grizzly bear attack near Yellowstone National Park and it made me wonder about you. It made me wonder about what you have done with the hard experiences–the grizzly stuff, I mean.

The story is quite remarkable by virtue of its simplicity. Two college-aged boys, Brady and Kendell, both junior college wrestlers— one pretty good and the other not-very-good—are traipsing around deep in the woods looking for “shed” (fallen deer antlers) when Brady inadvertently walks into a grizzly bear mother’s living room.

Within thirty seconds, massive mamma griz is on top of Brady tearing him apart. Punctures, lacerations, shattered arm, etc. Kendell hears the screams and throws rocks at mamma griz, to no avail.

Hours later, in the hospital, Brady’s father approaches the heavily wounded Kendell in tears: You saved my son’s life. I am forever grateful. You didn’t have to do that. No one would have faulted you.

In response, Kendell tells him, I knew I couldn’t live the rest of my life knowing that I could have done more to save my friend. So I jumped the bear.

There you have it. Kendell jumped the bear.

Mind you, Kendell was the not-very-good wrestler. But c’mon, it’s a grizzly bear, so it probably doesn’t matter. Kendell gets torn to shreds but distracts the bear enough to give Brady time to escape. The bear fight would resume for all three a few minutes later, but the boys escaped by sheer grit.

More Avoidance = More Fear

For me, the real gem of this story is what happens after the boys survive the bear attack.

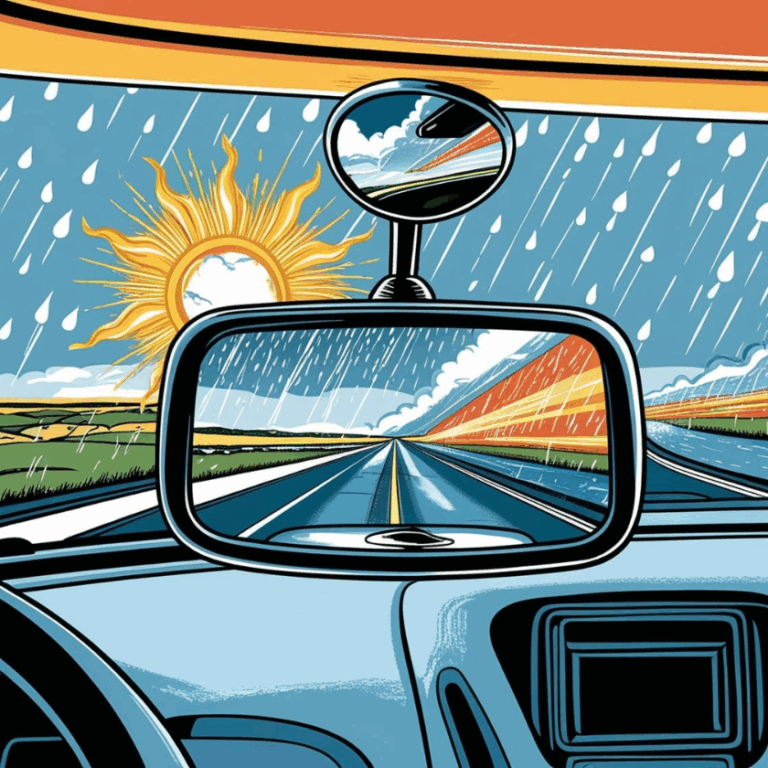

Months later, after recovering from their physical injuries, they go back to the mountain where they were attacked. Not the exact site, but close enough. They go deep into the woods together, looking for deer antlers. They stay close—nervous and fidgety and quiet—but they make it through. Why? Because, to paraphrase, they don’t want fear to shrink their lives, to narrow what is possible for themselves moving forward.

Perhaps they intuitively understand: more avoidance yields more fear.

So they dissolved the fear by going into it.

But they didn’t just revisit the site of the trauma. They let it transform them. Listening to them talk about it, you hear no victimhood. You don’t hear from them this hard thing happened to me. It’s more like, this is what happened. They weren’t the center of anything, just part of that particular moment in time.

Unlike many good folks who experience trauma, these boys didn’t want to return exactly to who they were before the attack. They knew they couldn’t. That innocence was gone…and there was nothing tragic about that reality.

Their junior college offered them free psychotherapy but they turned it down. Instead, they chose daily wrestling practice with each other (and teammates) over “talk therapy.” Their therapy was primal: the daily, disciplined grind of 5-mile runs followed by sweating, bleeding, and grunting with each other on the wrestling mat.

Brady got a massive tattoo of a grizzly bear head on his chest. Kendell, who didn’t need a bear tattoo thanks to the scythe-shaped facial scar left by griz mama’s teeth, now sports a massive bear paw tattoo on his back.

Months after the attack, and despite his injuries, Brady would return to wrestling and barely qualify for the state tournament. A low seed, he made an improbable run deep into the tournament. In tight moments on the wrestling mat, he’d unleash a newfound focused ferocity, echoes of the mamma griz within.

Kendell developed a quiet wisdom. You get a sense from him that he is the keeper of the sacred mantra they reflect to each other when one or both are struggling: keep moving forward.

Listening to their story, you can hear the desire to be transformed by the experience, not merely to be survivors. Somehow they know that the recipe for their healing and transformation lies in connecting deeply to the ways in which they feel primal and vitally alive.

And that includes accepting that the bear changed them.Subscribe

Unleashing Your Inner Bear

How did our ancient ancestors psychologically recover from violent attacks? Geez, their lives were filled with hardships and violence. Tribal histories are replete with stories of introjection–the embodiment of aspects of the thing that is bigger than you, so you can transform into something bigger than you were.

To keep moving forward the ancient tribes graduated you. Your identity expanded because of the hard experience. You developed a new part of your psyche: a wolf, a river, a spear, a leader, a matriarch, a bear. This expansion is the opposite of paralysis.

Paralysis happens when we get stuck on why did this happen to me?

Paralysis happens when we suppress traumatic experiences and, in the process, wreck our nervous systems.

So few of us have tribal mentors to graduate us. Instead, we have to initiate ourselves.

What if you believed that LIFE gives you that experience so you can develop yourself? Challenges you so you can refine very particular traits? What if you learn to embrace the hard experience and, because of it not despite it, you ripen very specific qualities that deepen your appreciation of life?

The hard thing happened, and now I’m changed. I must accept the change–and help it to ignite new potentials within me.

There’s a zen saying I love: the problem and the solution are one. In other words, the way out of the trouble is to be found in the particulars of the problem.

So…what if you graduated yourself? What if you saw the hard experience symbolically as a portal, beckoning for literal transformation?

If you are a parent or grandparent, how would the idea of “graduation” affect the way you shepherd your children/grandchildren through the inevitable small and large bear attacks awaiting them?

Would you say, You’ll be ok. I’m with you. Things will go back to just how they were.

Or might you say, You’ll be ok. I’m with you. You’ll recover. Some things will change…AND… now, love, you have the fierce loyalty and tenacity of a bear.

Hold high the lantern, friends.

Chuck