Even in This, There is Beauty

It’s not happening to us. It’s happening for us.

It’s not our world. Never was.

It’s easy to treat our misfortune like a sniper’s bullet. It feels personal and particularized for us even when it’s not. We rise limping and transformed…or limping and bitter.

Cancer. Freak injuries. Divorce. Depression. Anxiety. Exploitative work situations. Catastrophic weather damage. Moral injuries. And so on.

Once, teenage Joey failed to heed the Do Not Enter sign at the zoo and got mauled by a silverback gorilla. After my friends left me behind, I just said fuck it and went in, he would later say. The temptation to lean into darkness isn’t wrong, it just is.

The problem happens when we get stuck there. Little Joey became Big Joey with an enticing story to tell to win friends. Gorilla Boy, or something like that. But it never worked very well. So he just kept telling the story, sounding more and more desperate. He didn’t learn from the terror. Didn’t see life differently given another chance to live. He just wanted you to know he survived a gorilla mauling and maybe you’d appreciate him.

Enter Ahab, from the novel, Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s reflecting pool into your subconscious. Ahab, embittered from losing his leg to the great white whale, Moby Dick, launches a three-year vengeance odyssey in search of the whale. He even leaves his new wife and child for his mission of madness.

Ahab is instructive for us midlifers, for he shows what happens when we reduce ourselves to our pain. He doesn’t just lose his leg, he becomes the wooden leg, itself, constantly fidgeting and fighting with it, thereby filtering out any light that doesn’t illuminate the pain of the wound…and wrecks everyone’s life in the process.

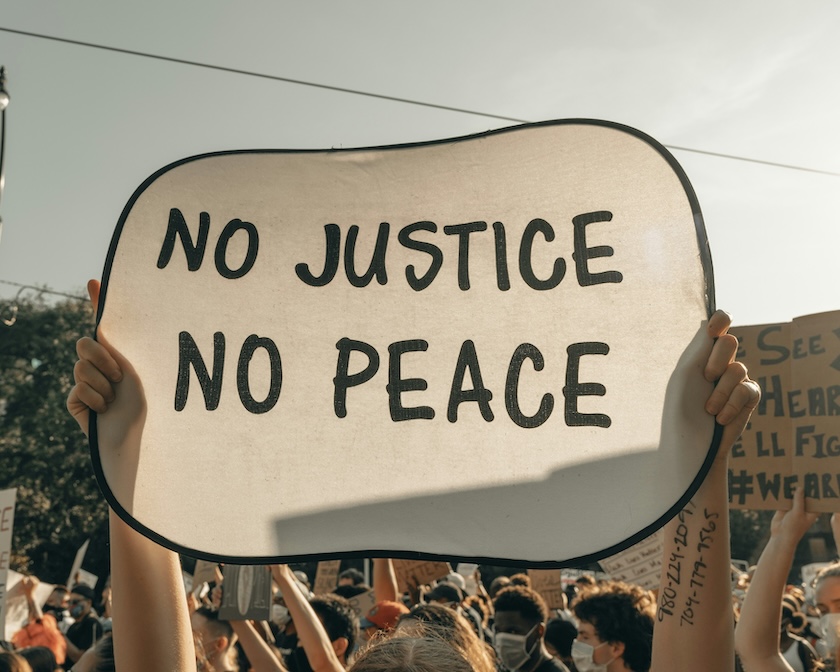

The last thing we want to hear as our inner Ahab patrols our ship decks is a way out of our pain. Vigilance and the need to be right surges dopamine in our brain, helping us feel powerful–a nice relief from the powerlessness that came with the injury. Shake that fist in the air! God knows I’ve done that a thousand times.

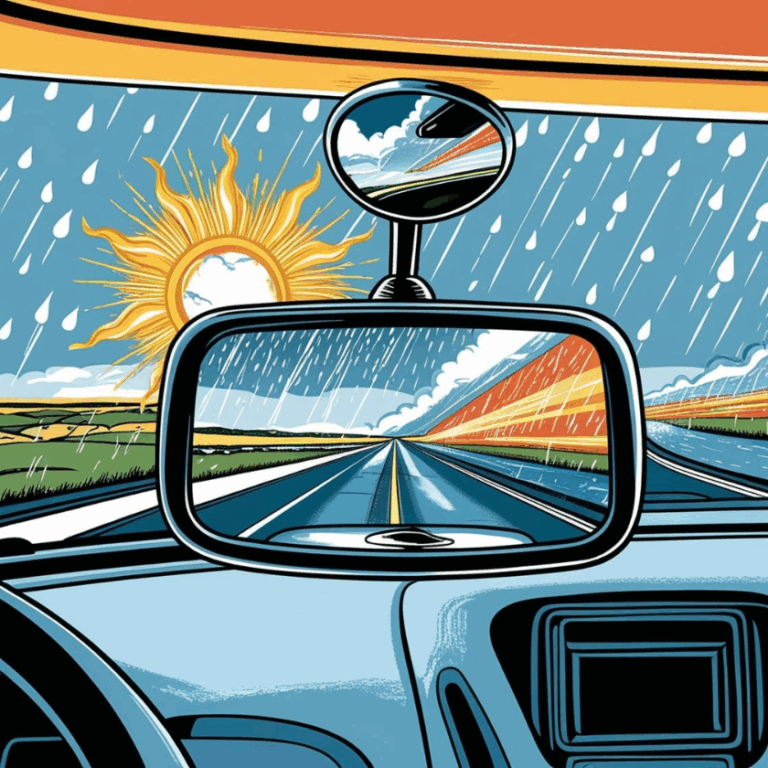

And yes, there are many pathways out of our pain stories even if our brain’s ancient wiring clutches fiercely to the negative. One pathway is so-called blessings. Not the formal anointing kind. More like the unexpected appearance of a doorway out of the small “pain story” room–and into a beachside tiki bar for the soul where you won’t get your amputated leg back, but you will occasionally feel the waves of the nearby ocean synchronize nicely with your resting breath. And that, alas, is enough. Perhaps with beer in hand!

Wisening Up Ahab

Meet midlifer, Tommy Rivers-Pulsey. “Rivs,” an endurance runner, cyclist, coach and much loved figure in endurance sports. Known for his generous and enthusiastic spirit, he contracted a rare cancer that has almost killed him several times. He knows it will kill him, perhaps soon. Listen to him share his story on the Rich Roll podcast, you’ll hear him accept that his time is short. You won’t hear bitterness.

In soft, deliberate tones you’ll hear him say, as if holding his broken body in his hands, even in this pain, there is beauty. For him, the beauty opens him–invites more living in his life. More willingness to touch others with love, to listen with compassion, to deepen sensuous relationships with the simple world around him: grass, chocolate, leaves, wind, toes in the sand, and so on.Subscribe

Rivs, among many others, points to the critical shift in consciousness: Seeing that the woundings, injustices, heartbreaks, unsolvable mysteries and sadnesses are not happening to him, but happening for him.

If we let them, they will put more living in our life. Tiki bars and ocean breezes for the soul.

By midlife, we’ve been thumped by a few white whales and more thumpings will happen. The temptation is to shrink and hide, or fight back. Though I believe there is a place for righteous resistance, if we want to avoid living from the Ahab within, we mustn’t become the fight, the bereavement, the heartbreak, the exploitative situation, etc. We mustn’t allow it to become who we are, our cursed wooden leg. We mustn’t lose our sovereignty.

We mustn’t allow the wounded part to become our whole.

It’s not our world. Never was. In our suffering, when we meet life on its terms–and not ours–we are better able to hear the click-clack of our wooden legs on the ship deck, wince, and then choose to return the ship to shore, all the while enjoying the taste on the tongue of the ocean’s salty mist and the beckoning of seagulls guiding the way home.

Even in this, there is beauty.

Hold high the lantern, friends.